Who is Eduardo Francisco Costantini?

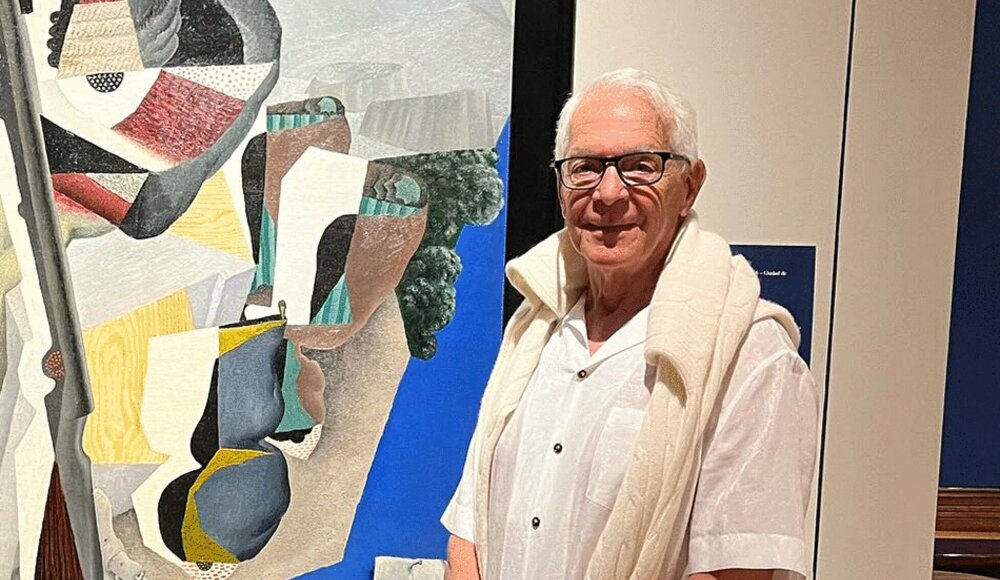

Eduardo Francisco Costantini, born on September 17, 1946, is an accomplished Argentine entrepreneur primarily involved in real estate development. He is also renowned as the creator and leader of the Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires (MALBA). As of April 2022, his total wealth was appraised to be approximately $1.6 billion.

A deep passion for advancing Latin American art and culture

Eduardo F. Costantini develop a deep passion for advancing Latin American art and culture. He is not only recognized for his significant contributions to real estate but also as the visionary behind the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (abbreviated as MALBA), which is supported by the foundation bearing his name.

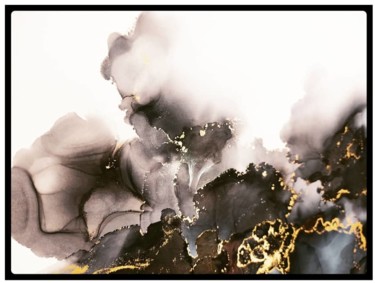

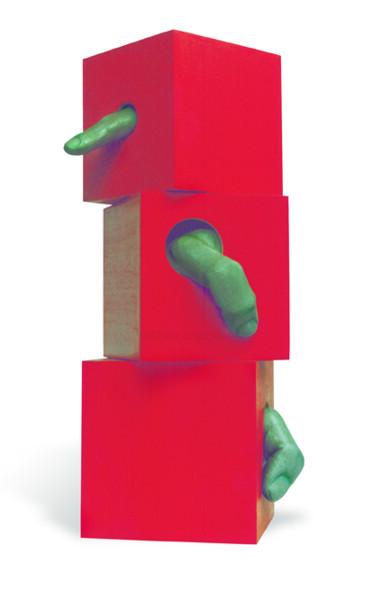

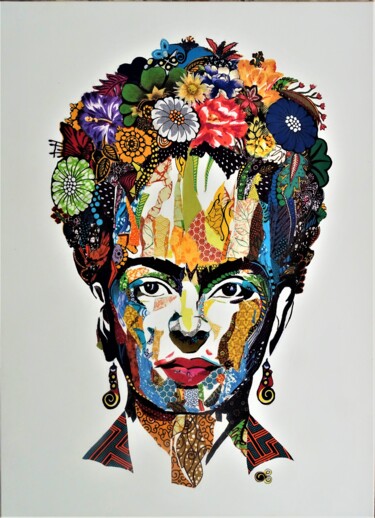

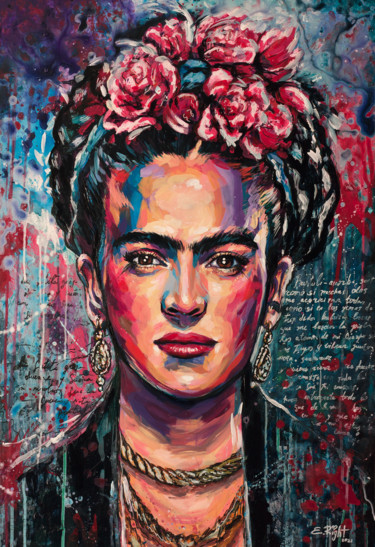

In 2001, Costantini made a generous donation of over 220 Latin American artworks to the museum, including pieces by celebrated artists like the renowned couple Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. Among these acquisitions, he secured Diego Rivera's masterpiece, "Baile en Tehuantepec," which became a prized possession in his extensive art collection. Valued at around $24 million, it briefly held the title of the most valuable artwork among his impressive collection. However, the pieces he holds most dearly are two creations by the esteemed Argentinian artist León Ferrari.

It took Costantini five years of persuasion to convince Ferrari to part with his hanging sculpture, "Gagarín" (1961), and the intricate text work, "Cuadro escrito" (1964). When asked about his recent art acquisitions in 2019, he mentioned "Simpatía (La Rabia del gato)" by the Spanish Surrealist Remedios Varo, whose popularity had been steadily increasing. This painting was acquired for slightly over $3 million.

In his professional career, Costantini has played a pivotal role in developing some of Buenos Aires' most iconic buildings, including Catalinas Plaza in 1995 and Alem Plaza in 1998. In 2009, he initiated the Oceana project in Bal Harbour, which was successfully completed in 2015, featuring condominiums with prices reaching up to a remarkable $19 million. Notably, the outdoor space of the tower is adorned with two sculptures by Jeff Koons, with ownership shared by the residents.

Costantini's art collecting endeavors have not only enriched his personal collection but have also contributed to the broader art market. In 2020, he acquired Wifredo Lam's "Omi Obini" (1943) and Remedios Varo's "Armonía (Autorretrato Surgente)" (1956) at Sotheby's for a combined total of $15.8 million. Lam's work set a record as the most expensive piece by a Latin American artist ever auctioned at that time. Two years later, Varo's painting was prominently featured at the Venice Biennale in Italy. Furthermore, in 2021, Costantini acquired Frida Kahlo's "Diego y yo (Diego and I)" (1949) at a Sotheby's auction for an astounding $34.9 million, surpassing the record previously held by the Lam painting. "Diego y yo (Diego and I)" now proudly stands as the most valuable treasure in Costantini's remarkable art collection.

About Malba

The MALBA, which stands for the Museum of Latin American Art of Buenos Aires (Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires in Spanish), is a prominent cultural institution in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Situated in the upscale Palermo neighborhood, this private museum boasts an extensive collection of contemporary artworks created by Latin American artists. The journey of MALBA began in 1996 when the art collection of Argentine philanthropist Eduardo Costantini was first unveiled to the public. This initial exhibition took place at the National Museum of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires and the National Museum of Visual Arts in Montevideo, Uruguay. The overwhelmingly positive response to this showcase led to the concept of establishing a permanent exhibition space to house these remarkable artworks.

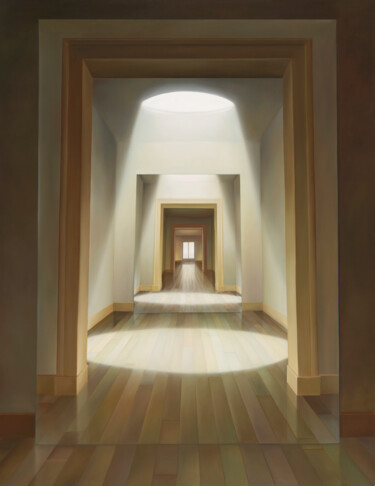

In 1998, a plot of land was acquired in Buenos Aires' Palermo district, and an international competition was organized to design the museum's architectural structure. The winning proposal was submitted by a team of three Argentine architects: Gastón Atelman, Martín Fourcade, and Alfredo Tapia.

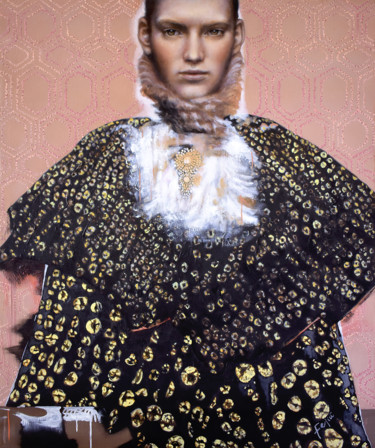

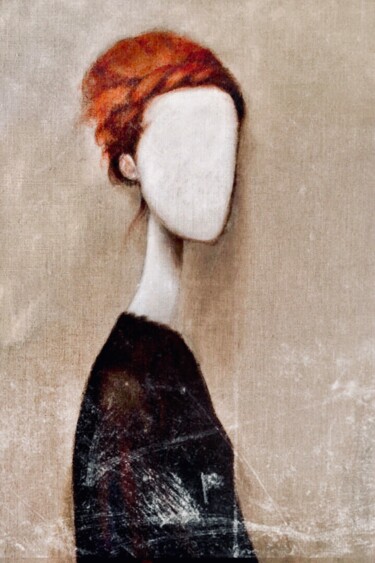

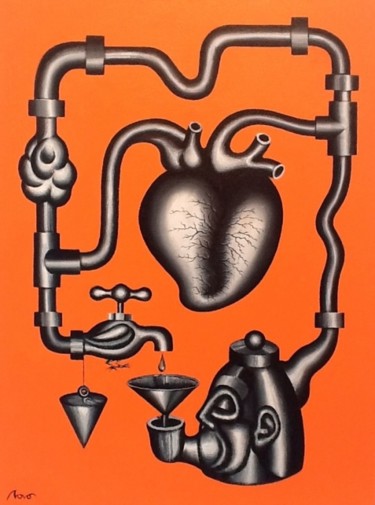

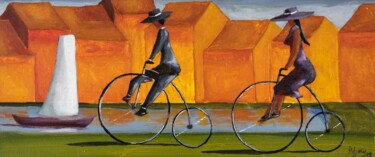

On September 20, 2001, the museum officially opened its doors to the public. MALBA serves as the custodian of the Costantini Collection and regularly hosts temporary exhibitions featuring the works of Latin American artists. Some of the prominent artists whose works are displayed include Frida Kahlo, Roberto Matta, Pedro Figari, Tarsila do Amaral, Guillermo Kuitca, Jorge de la Vega, Linoenea Spilimbergo, Antonio Berni, Emilio Pettoruti, and Fernando Botero. Beyond its visual arts offerings, the museum also houses two significant sections dedicated to cinema and literature.

Its remarkable collection spans the significant trends and artistic movements that have shaped the past century in a youthful region caught between the sway of European avant-garde movements and the development of a distinct local artistic style. Further insights can be found in the in-depth interview with Marcelo Pacheco, who leads the curatorial department at this Argentine museum.

The Malba is home to Eduardo Costantini's collection of contemporary Latin American art. How did the idea of creating this museum come to fruition?

In fact, the Malba currently boasts a collection of 500 artworks, with 220 of them originating from Eduardo Costantini's collection. These pieces formed the initial endowment of the institution and continue to constitute the museum's most significant core. Costantini emerged as one of the prominent collectors of Latin American art in the early 1990s, both within the local and international art scenes. His collection has always been accessible to specialists, whether they are local or foreign, and it has maintained a very generous lending policy.

In 1996, the collection was publicly exhibited for the first time in a show at the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires. The collection's inclination toward the public domain has been evident from the very beginning. Interestingly, the concept of the museum's creation originated from a pivotal non-artistic event. In 1996, an opportunity arose to acquire a piece of land at the intersection of Avenida Figueroa Alcorta and Calle San Martin de Tours, situated in the upscale residential neighborhood of Palermo Chico, the most sought-after area in Buenos Aires. When Costantini saw this location, he immediately envisioned the construction of a museum. It was the final available plot on Avenida Figueroa Alcorta. Following the acquisition, he established the Eduardo F. Costantini Foundation, providing the museum with its legal framework.

The Malba boasts an ultra-contemporary architectural design that seamlessly integrates with its surroundings. Could you provide more insights into the project?

The museum's architectural design emerged as the outcome of an international competition organized by the foundation and overseen by the International Union of Architects, with Sara Topleson serving as the jury's president. Remarkably, the winning proposal came from a relatively young architectural studio based in Cordoba, Argentina, comprising three architects: Gastón Atelman, Martin Fourcade, and Alfredo Tapia. Situated along one of the city's most significant cultural corridors, the museum's location spans from the Retiro neighborhood to the gardens of Palermo. This cultural route includes the Museum of Hispanic American Art, renowned for housing the continent's most extensive collection of colonial silverware, and encompasses various other prominent institutions such as the National Exhibition Halls, the Recoleta Cultural Center, the National Museum of Fine Arts, the National Museum of Decorative Arts, the Museum of Popular Motifs, Malba itself, and the Municipal Museum of Fine Arts, all nestled within the lush woods of Palermo.

Could you elaborate on the artistic movements that constitute the museum's permanent collection? What is the unique identity and character that Malba offers to its audience?

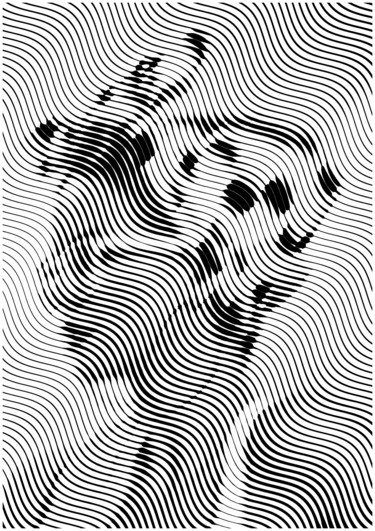

The distinctiveness of Malba primarily resides in its collection, entirely dedicated to Latin American art, spanning from the early 20th-century avant-garde movements to contemporary creations. It stands as a unique institution worldwide, singularly committed to showcasing art produced from Mexico to Buenos Aires, from Havana to Santiago de Chile. The collection encompasses a wide spectrum of modern and contemporary artistic currents that have gained international acclaim, ranging from Cubism to Conceptual art, Transavantgarde, Surrealism, Social Realism, Concretism, Neo-Concretism, Optical art, Kinetic art, New Figuration, Pop art, and Hyperrealism. These movements are presented through the lens of Latin American artists, developed during their experiences in Europe and New York, as well as upon their return to their home countries. This results in distinctive amalgamations that span from Americanism to Criollo, encapsulating avant-garde qualities from diverse modernities. Moreover, the collection includes movements that originated specifically in Latin America, such as Vibracionismo, Nativism, Neocriollismo, Anthropophagy, Mexican Muralism, New Realism, Generative art, Madí movement, Systems art, among others.

Do you have any plans for new acquisitions? Where do you source artworks?

Between 2002 and 2011, the museum significantly expanded its collection through an acquisitions policy, generous donations, and active participation from the "Asociación Amigos del Malba" along with supplementary funds. However, due to budget constraints – the total available fund in 2009 was reduced to $120,000 – most of the acquisitions were primarily focused on local artists. There were exceptions, such as works by Gabriel Acevedo Velarde and Bryce from Peru, Luis Camnitzer and Alejandro Cesarco from Uruguay, Francis Alÿs from Mexico, Artur Lescher and Ana Maria Maiolino from Brazil. In 2013, with the foundation now in place as a source of funding, the "Asociacion de Amigos" established an acquisitions committee composed of around thirty individuals, in addition to the Foundation. This committee aims to return to the original trajectory of the Costantini collection by acquiring works from artists in various countries within the region.

Malba remains open to all the possibilities offered by the art market, primarily acquiring artworks from art galleries, auction houses, or directly from artists. One of the factors limiting international acquisitions is the costs associated with transportation and customs duties for permanently importing artworks, elements that significantly impact the pricing of selected artworks.

In addition to the opportunity to explore the permanent collection on display in the main hall and the rotating temporary exhibitions, what other activities does the museum undertake, and what are its primary goals?

Malba is actively involved in an extensive educational program that encompasses guided tours of both the permanent collection and temporary exhibitions. Specialized tours are also offered to schools, individuals with visual or hearing impairments, retirees, students, and families. Notably, the school program places a special focus on serving the student population in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods of the city, and during the summer, it extends its outreach to state-run summer camps. Beyond the departments and spaces dedicated to visual arts, Malba includes dedicated departments for cinema and literature. These three disciplines occasionally collaborate on joint projects and curatorial initiatives. They offer a range of programs, including lectures, courses, hosting international guest speakers, curating a film library, publishing initiatives, preservation efforts for audiovisual heritage, and the release of DVDs featuring thematic cycles dedicated to Latin American authors. The museum's bookshop also actively contributes to promoting Argentine and Latin American industrial design by commissioning unique objects that are available for purchase on-site.

Across all areas of the museum, the overarching objective is to further the mission of the Constantini Foundation. This mission revolves around promoting, disseminating, and enhancing the visibility and appreciation of Latin American art, both locally and internationally. Malba stands apart as an institution that doesn't solely receive and showcase offerings from international art circuits; rather, it plays an active role in producing exhibitions, film series, lectures, literature courses, and maintains a substantial publishing program that includes catalogs and art books, among other publications. The museum's auditorium currently holds the distinction of being the most important private venue for independent cinema in the country. Additionally, the literature department organizes the International Literature Festival FILBA every two years. Thanks to its diverse and extensive educational offerings, Malba has earned recognition as the Argentine museum with the highest level of accessibility for the public.

As for funding, the Constantini Foundation's financial support is derived from various sources. Nearly 50% of Malba's annual costs, which amount to approximately three million dollars, are generously provided through the personal contributions of its founder and president, Eduardo F. Costantini. The remaining 50% is funded through revenue generated by ticket sales, institutional and private sponsorships, bookshop sales, and a concession fee from the bar-restaurant.

Interview with Eduardo F. Costantini

While many collectors choose to donate their artworks, what prompted you to conceive the idea of establishing an entire museum to showcase your collection?

I had already contemplated the notion of donating my collection, but initially, I envisioned doing so posthumously. However, as a real estate developer, I stumbled upon a piece of land available for purchase, and I thought to myself, "This is a unique opportunity that may never arise again, situated in a prime area of Buenos Aires, surrounded by other museums. This is what I must undertake." Subsequently, I experienced a period of mild depression and conflicting emotions for about a week because I felt as if I were a living corpse. In my mind, I had linked the act of donation with death, which in retrospect, seemed rather nonsensical. Soon enough, I came to realize that it was precisely the opposite – that a museum signifies life. It thrives through the involvement of people; the community and its activities breathe vitality into art, making it far more potent and enriching than merely having artworks displayed on the walls of one's home.

Do you think culture can survive and thrive without government funding and protection?

I believe that the government plays a crucial role, but it's a matter of finding the right balance. The private sector also bears responsibility in supporting culture, much like it does in areas such as healthcare and research. Both sectors have their roles to play, and the key is to strike a balance. We shouldn't be rigid in our thinking about this. It's intriguing how you approach this as a matter of obligation and moral duty. Indeed. Humans have a social role that they must fulfill. In Latin culture, there's often a strong focus on the family, similar to what's portrayed in patriarchal Italian families in mob movies, where someone might commit serious deeds but then seek solace in prayer and share a meal with their family as if everything is resolved. I believe that Latin culture sometimes leads us to prioritize our obligations to our family over those to society. This is also reflected in the law, which mandates that you must leave two-thirds of your assets to your family, even if you have a strained relationship with a family member. In contrast, Anglo-Saxon culture provides more independence in deciding how to allocate your assets, placing greater emphasis on social responsibility. In the United States, for instance, it's almost frowned upon if you're a millionaire and not involved in charitable institutions or philanthropic activities. Encouraging such engagement is something that should be promoted more in Argentina. Here, whether you purchase ten luxury cars or donate the money to a hospital or museum, the tax implications are the same, leading to a lack of tax incentives for philanthropy. I believe this needs to change. In a capitalist society where the private sector holds substantial wealth, there should be more encouragement for private investment that complements public initiatives.

Lorca and García Márquez, among others, expressed that they wrote to be loved. Why do you collect?

I collect because I have a deep love for art. Additionally, I've discovered a social purpose in collecting that I can no longer ignore. When I acquire a piece of art, I envision it being displayed for others to appreciate. There are even artworks I purchase without seeing them personally, and I've lent pieces to institutions for exhibition before having seen them myself. My perspective on collecting now encompasses both a personal and institutional dimension.

When and why did you decide to start collecting?

My journey into collecting art was entirely spontaneous, without any predefined strategies. In my early twenties, I happened to pass by an art gallery while on my way to an ice cream parlor. I went inside, and despite having limited funds, I made my first art purchases through installment plans. No one in my family was involved in art collecting. But from that moment onward, I continued to make occasional art acquisitions. It was only in the 1980s that I realized I was evolving into a collector, despite that initial purchase back in the late 1960s.

You made the early decision to specialize your collection in iconic Latin American art pieces. What drove this choice?

Primarily, it stemmed from my Argentine identity, making me inherently part of the Latin American context. I believed that my collection would gain depth and significance by assembling the most prominent artists from the broader Latin American region to which Argentina belongs. Despite the variations among Latin American countries, there are shared themes and issues that make this focus both compelling and coherent. Moreover, strategically speaking, I saw that my collection could have a more prominent presence by uniting outstanding works from the masters of Latin American art. It was a journey that, like any well-conceived project, gradually evolved and crystallized over time.

How has your relationship with art and your role as a collector developed since then?

It's been a process of steady growth. Collecting resembles constructing a building – you keep adding pieces, never retracting, constantly accumulating. Over the years, I've come to realize that the collection has accrued cultural, artistic, and social value. Eventually, the idea emerged to donate it to an institution. Initially, I had envisioned it being a public institution, but later, I came to the conclusion that creating a private institution focused on Latin American art would be more beneficial. The core idea was for the collection to grant the institution a distinct identity and strength. The collector's role then transformed into that of a guardian of the museum, with the museum's mission being the promotion of Latin American art and the attraction of a wider audience.

Has the Malba museum evolved in tandem with your journey?

The museum quickly began engaging in loans and collaborations with other provincial, national, and international institutions. Simultaneously, we developed programs encompassing literature, a film festival, educational initiatives, and bolstered our collection through acquisition programs, an association of friends, and a dedicated board. The evolution over these past 20 years has been quite rapid. Interestingly, we are also in the process of establishing a second Malba location.

If I'm not mistaken, this new project is designed by the Spanish architect Juan Herreros, known for his work on projects such as the Munch Museum in Oslo. When is its opening scheduled?

Our plan is to inaugurate it in April 2024. It will be named Malba Puertos and will be situated in the Buenos Aires province, with a greater focus on contemporary art.

Do you believe that art has the potential to bring about social improvement or to change the world or people's perspectives?

There is often criticism aimed at those who believed that art could change the world and found it fell short. Art, like all forms of human expression, can range from being entirely neutral to deeply political, or it can carry messages with idealistic or harmonious inclinations, even without explicit political intent. In any case, I firmly believe that art dignifies humanity. Museums serve as secular temples of postmodernity. At Malba, we offer a neutral platform for art. We embrace diverse perspectives as long as they involve good art. We do not take a specific stance.

Do you believe that collectors should have a social role, then?

Absolutely. However, it's important to note that not all collectors embrace this social responsibility, as some approach collecting as a self-centered and individualistic pursuit. They may choose not to lend their artworks, keeping them hidden away. Occasionally, an artwork that was absent from the public eye for decades reemerges when its owner passes away and it reenters the market. I've witnessed this happen myself.

Selena Mattei

Selena Mattei